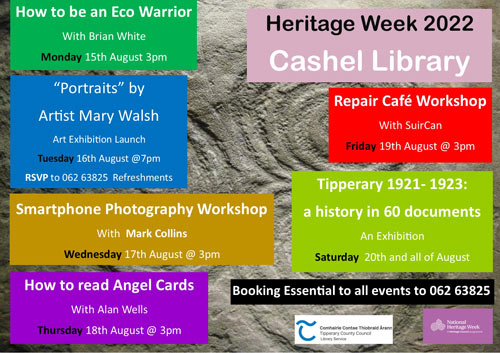

Note Please: Booking Essential To All Events.

RSVP to Tel: 062 63825.

|

|||||

Note Please: Booking Essential To All Events. A remembrance ceremony, latter marking the centenary of the death of Arthur Griffith, will take place today, at Leinster House. Arthur Joseph Griffith was born at No.61 Upper Dominick Street, Dublin, on March 31st, 1871, of distant Welsh lineage. His father had been a printer on ‘The Nation‘ newspaper.  Educated by the Irish Christian Brothers, he became the founder of the Sinn Féin party. In 1916, rebels seized and took over a number of key locations in Dublin, in what became known as the 1916 Easter Rising. After its defeat, it was widely described both by British politicians and the Irish and British media as the “Sinn Féin rebellion”, even though Sinn Féin had very limited involvement. Griffith would be one of those arrested following the Rising, despite not having taken any part in it. Arthur Griffith later served as Minister for Home Affairs from 1919 to 1921, and Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1921 to 1922. In September of 1921, Éamon de Valera, the then Irish President, requested Arthur Griffith, to head as Chairman a delegation of Irish diplomats, invested with the full power of independent action, to negotiate on behalf of the Irish people, with the British government, in the setting up of an Irish Republic. This delegation set up headquarters in Hans Place, London, and following nearly two months of negotiations, on December 5th, Griffith and the other four delegates decided, in private conversation, to sign a Treaty before recommending same to Dáil Eireann. The Treaty was then ratified by the Dáil by 64 votes to 57, on January 7th 1922. Two days later, Éamon de Valera stood down as president and sought re-election by the Dáil, which he lost by a vote of 60 to 58. Mr Griffith then succeeded Mr de Valera as President of Dáil Éireann. Despite the Treaty being narrowly approved by the Dáil, a political split would lead to the Irish Civil War. Griffith, at the age of 51 years, sadly died suddenly in August 1922, two months after the outbreak of the civil war. He had been about to leave for his office, shortly before 10:00am on August 12th 1922, when he paused to retie a shoelace and fell, slipping into unconsciousness. He did regained consciousness, but collapsed again with blood coming from his mouth. The cause of his death, was identified as cerebral haemorrhage. His death came, just ten days before the death of Michael Collins, latter who lost his life following an ambush in Co. Cork; seen then as a double tragedy to befall a fledgling independent Irish State. Arthur Griffith’s body, four days following his death, was interned in Glasnevin Cemetery. The idiom “Eaten bread is soon forgotten”, was never truer, as was in his case. His widow had to beg his former colleagues for a pension, saying that he ‘had made them all’. She also considered that his grave plot was too modest and threatened to exhume his body. It took until 1968 before a plaque was finally attached on his former home, situated at St. Lawrence Road, Clontarf, Dublin. The book entitled “Journal of A tour in Ireland” was written by Sir Richard Colt Hoare, Bart. F.R.S. F.A.S.*, and Published 215 years ago, in 1807.

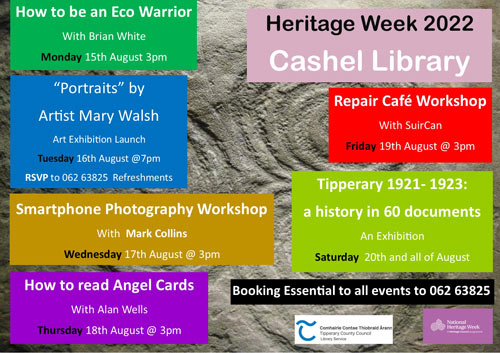

The book once graced the library owned by Captain Richard Carden, Esq, Fishmoyne, Drom, Kilfithmone, Thurles, Co. Tipperary; latter Captain of the Tipperary Militia and today remains part of a private Tipperary collection. Captain Richard Carden: Captain Richard Carden was the son of Minchin Carden and Lucy Lockwood, and as already stated was born at Fishmoye, Drom, Co. Tipperary, Ireland, c 1760. Richard Carden, the former, passed away on February 7th, 1812, aged 53 years, and is interned in Saint Michan’s Church, Church Street, Dublin 7. Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s Tour. The tour of parts of Ireland, by the above author, including some areas of Co. Tipperary; had taken place the year before, (1806) and the opening Preface of the book, bears the Latin headline; “Erranti, passimque oculos per cuenta tuenti”, (Translated: “Wandering, keeping his eyes here and there”.), gives us a certain insight into what life was like and how Ireland was viewed by the gentry, some 216 years ago. Quote from the Preface; “To the traveller, who fond of novelty and information, seeks out those regions, which may either afford reflection for his mind, or employment for his pencil and especially to him, who may be induced to visit the neglected shores of Hibernia*, the following pages are dedicated“.

Author Sir Richard Colt Hoare continues: “The island of Hibernia (Ireland) still remains unvisited and unknown. And why? Because from the want of books and living information we have been led to suppose the country rude, its inhabitants savage, its paths dangerous. Where we to take a view of the wretched conditions in which the history of Ireland stands, it would not be a matter of astonishment that we should be considered as a people, in a manner unknown to the world, accept what little knowledge of us is communicated by merchants, sea-faring men and a few travellers. While all other nations of Europe have their histories, to inform their own people, as well as foreigners, what they were and what they are. We will discuss more details on Sir Richard Colt Hoare’s tour of Tipperary in the coming days.

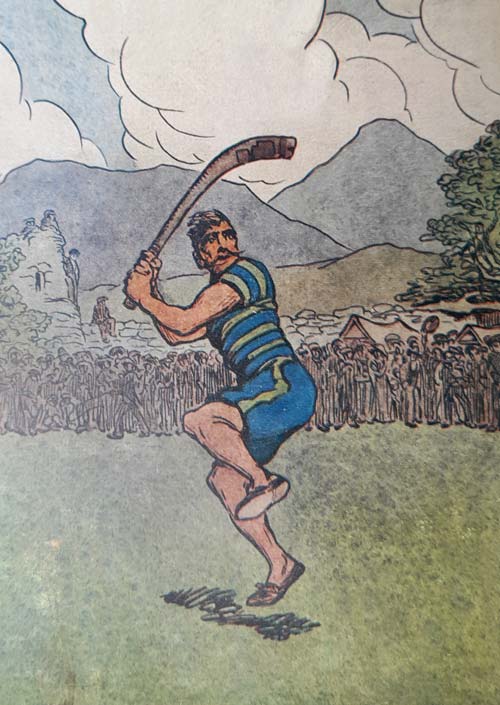

“The Man From Thurles” [Extract from the scarce antiquarian book published in 1912, entitled “Rambles In Ireland”, by author Robert Lynd.] I met the man from Thurles, in Kilkenny, as I was going up to the station from the Imperial Hotel. He was old and shuffling, a ragged creature that once was a man and now humped from town to town with a spotted red handkerchief in his hand, gathering the needs of his belly from among those things that we others do not require for our dogs.  He was as hairy and weather-beaten as a sailor, but he was still like a squeezed and shrivelled sailor. His dark hair and beard were as limp as weed. His eyes, which looks like the eyes of a blind man, with the lids falling down on them as if in deadly weariness, might have belonged to one who had been captured by Algerian pirates in his youth and who had lived in dungeons. He was wearing a tattered ‘wideawake’ * a symbol of homelessness and as he walked, he seemed to put his feet down with uncertainty, like a drunken man.

I stopped him to ask whether a church set high amongst gravestones by the side of the road was the Black Friary – I think that was the name of the place. He made me repeat my question and then in a monotonous voice told me – that I could see for myself – that it was a graveyard in there, mumbling something about Protestants and Catholics both being buried in it – “side-by-side,” – he added for the sake of euphony. Obviously, he had not heard any question or did not know the answer to it. But that did not matter. I really did not care twopence about the Black Friary. He went on to say that he was a stranger in Kilkenny and (without ever raising his flyblown eyes) that he had only arrived there that day after a walk of 30 miles. Suddenly his appearance changed; his bold Jekyll collapsed into a whining Hyde. I should not have been surprised if he had put his hand into mine for comfort like a frightened child. He held his breath as the policeman, a bold-boned figure in dark green, trod past. Then he let his breath out again. “They’re tyrants, them fellows”, he said “and the lies they would tell on a poor man might be the meaning of getting him a week or maybe a month in jail, and he after doing nothing at all, but only going quietly from place to place. And thieves and robbers running loose that would murder you on the roadside and no one to say a word”. I asked him to come into a public house for a bottle of stout, but he said that a bottle of stout would make him light in the head. At length, however, he said he would come and have a glass of ale, if I was sure I could keep the police from annoying him. I gave him my promise and we went in. “What do I mean?” he said, when I bought him back to the militiamen. “This is what I mean. I had a fine blackthorn stick one time”, he called it a “shtick”- “a shtick I had cut from the hedge with mine own hands and seasoned and polished, and varnished till it was the handsomest stick ever you seen. Well, I was walking along the road in this part of the country one day, when who should meet me but two of these milishymen. ‘Give us baccy’, said one of them – that’s what he called tobacco. ‘I have no tobacco’, said I. ‘You lie’, says he, rising his fist, to threaten me. ‘It’s the truth’, said I, putting up my arm to protect myself”. The old man half lifted the glass with his withered arm to his lips and half stooped his withered face to the glass. Having drunk, he wiped his mouth on his sleeve. To him a shilling was something considerable. It represented life for two days; he could exist, he told me on sixpence a day, in a place like Kilkenny. Twopence was the price of a bed in straw on the floor, where the rats ran across you, till you dreamed you had fallen in the middle of a fair and that all the beast were trampling over you. Then in the morning there was a penny for tea, a penny for a slice of bacon, a penny for bread, a halfpenny for sugar and a drop of milk, and a half penny for the loan of a can to make the tea in and a share of the fire. If he had bed and breakfast, he said he did not mind about the rest of the day. He never felt hungry as long as he had his cup of tea in the morning. Sunk to the hovels, though he was, he had the rags of a finer past about him. He used to be the best slaner, he assured me, in the north of Tipperary. “There’s a man I was at school with in Thurles living in this town”, he went on adding proof to proof of his original respectability, “a rich man, and, what’s more a giving man, and you’ll think it a queer thing, but I have only to walk up to the door and ask if he is in to get all I want to eat and drink and money, too, maybe sixpence into my hand and I going away, to put me a bit along the road. But I wouldn’t go near him”. “And why do you not go to him?” I asked again.

“But why don’t you go and see him? I persisted. There was something puzzling about the old man. It may have been merely his timid and indirect spirit. I doubt if he had the heart to beg – at least openly – either from a lifelong acquaintance or from a stranger. THE END  The first in-person Citizenship Ceremonies in over two years will be held on Monday, June 20th 2022, in the INEC Arena, Gleneagle Hotel, Muckross Road, Killarney, Co. Kerry. The ceremonies will be held at 11.00am and 1.30pm with registration for the first ceremony beginning at 10:00am and the second ceremony at 12.30pm on Monday, of the aforementioned date. Minister for Justice Mrs Helen McEntee TD, together with retired High Court judge Mr Bryan MacMahon and retired District Court judge Mr Paddy McMahon will be presiding over the ceremonies and conferring Irish citizenship on an expected 950 people. Ireland is a sovereign, independent country and has rules and laws about who is entitled to Irish citizenship. Most Irish citizens were automatically Irish when they were born. Before January 1st 2005, everyone born on the island of Ireland was an Irish citizen by birth. However, following an amendment to the Constitution of Ireland, citizenship by birth is now no longer an automatic entitlement to everyone born on the island of Ireland. If you are born abroad, you are entitled to Irish citizenship if your parent was born in Ireland. If your grandparents were born in Ireland, you may also be able to claim citizenship through the Foreign Births Register. Residents of Ireland who have come from abroad can apply to become Irish citizens, through naturalisation. Citizens of Ireland are also EU citizens, which means that they can live, work and study in any other EU member state. |

|||||

|

Copyright © 2025 Thurles Information - All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy | Disclaimer Powered by WordPress & Atahualpa |

|||||

Recent Comments