Jesuit priest, Fr Michael Bergin, William Maurice Armstrong, Sir Sackville Hamilton Carden KCMG , are just some of the Tipperary men, numbered among the many, whose heroics, Australians celebrated yesterday in their Anzac Day commemorations.

The acronym ‘ANZAC‘ stands for Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, whose soldiers were known as Anzacs. Anzac Day still remains one of the most important national occasions for both Australia and New Zealand, who remember the thousands of soldiers from all countries who lost their lives in the Gallipoli campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign, which took place between 25th April 1915 and the 9th January 1916, during the First World War.

This eight month campaign during the First World War, which was an attempt to seize obvious strategic advantage and was authorised by the British, with an attack on the Turkish peninsula, aiming to capture Constantinople.

By the end of this bitter eight month campaign estimated deaths would read as follows:

Turkey 86,692, British (Including Irish Men) 21,255, France 9,798, Australia 8,709, New Zealand 2,701, India 1,358, Newfoundland 49.

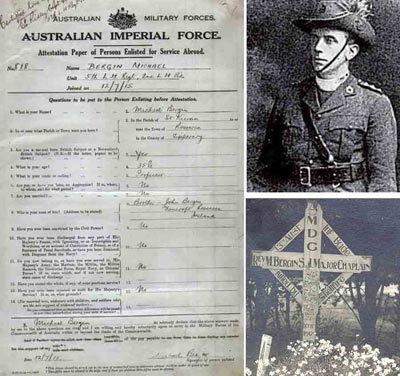

Professor Fr. Michael Bergin, S.J., M.C.(1879 – 1917)

Fr. Bergin won a military cross posthumously for his work as chaplain and as stretcher-bearer with the Fifth Light Horse Brigade.

Fr Michael was well travelled and born in Fancroft, near Roscrea, Co Tipperary, schooled in Mungret College Limerick, an Irish Jesuit chaplain with the Australian Imperial Force, which he joined as a trooper (stretcher bearer) to the 5th Light Horse, in order to accompany the Australians to Gallipoli.

He was the only Australian chaplain to have joined in the ranks, the only one never to set foot in Australia and the only Catholic chaplain to have died with the AIF (Australian Imperial Force). He always aimed to be where his men were in greatest danger, and having survived the Turkish campaign, he was killed by a German shell on the Ypres salient in Flanders.

The citation for the Military Cross awarded posthumously (although based on recommendation prior to his death), reads: “Padre Bergin is always to be found among his men, helping them when in trouble, and inspiring them with his noble example and never-failing cheerfulness.”

Fr Michael’s grave maker at Passchendaele, Belgium, gives the dates of his death as the 11th October. All official records indicate he died on the 12th October.

Captain William Maurice Armstrong, M.C. (With Bronze Oak Leaf )

Capt Pat, as he was known to his men served with the 10th (Prince of Wales’s Own Royal) Hussars. He was born 20th Aug 1889, the only son of Marcus Beresford Armstrong, Capt, D. L, J. P, of Moyaliffe, Co. Tipperary and Rosalie Cornelia, daughter of the late Maurice Ceely Maude, of Lenaghan, Co. Fermanagh, and cousin to Lieut. General Sir F. Stanley Maude, K. C. B, C. M. G, D. S. O.

He was educated at Stoke House, Slough and Eton and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He was gazetted 2nd Lieut. 23rd Feb. 1910, promoted Lieut 1st Feb 1914, and Capt. 7 May, 1917. He served with his regiment in India and South Africa and was in England on leave at the outbreak of war, leaving for France in Aug. 1914, with the original Expeditionary Force, being attached to the staff of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade.

After serving in France and Flanders, he was sent to Gallipoli in June 1915, where he served as Staff Captain, with the famous 29th Division, under Major-General Beauvoir de Lisle taking part in the evacuation of both Suvia and Helles. He was then sent to Egpyt and returned to France in March 1916, serving as Brigade Major. He had just been recommended for the D. S. O. when he was killed in action at the age of 28, on 23rd May, 1917, while on duty in a front-line trench near Arras. Buried in Fambourg d’Amiens Cemetery, Arras, Capt. Armstrong was awarded the Military Cross (London Gazette, 2nd Feb. 1916), and was four times mentioned in Dispatches (London Gazettes, 9th Dec 1914; 28th Jan 1916; 13th July 1916, and 15th May 1917), for gallant and distinguished service in the field.

In his private life he was a keen sportsman and very successful in his big-game shooting expeditions. He had won many races and horse-jumping competitions; was a promising polo player, and had hunted with most of the English and Irish hunting packs.

A General commanding the Cavalry Corps wrote; “As an old Tenth Hussar, too, I can tell you how very distressed the whole regiment will be, and what a loss he will be to them. He had done so awfully well during this war, and showed such great promise for the future, that he is a great loss, not only to his regiment and the cavalry, but to the whole army.

I do not know of anyone of his age who had a more promising future before him, as did he love his profession, and show most of the qualities needed for him to shine in it, but he had such a charming personality that all he came in contact with loved him, and were able to show their best work when working with him or under him.”

General de Lisle wrote: “He was so absolutely fearless, he was bound to be hit sooner or later, but I had always hoped it would be to be wounded only. You see the boy is referred to as ‘Dear old Pat,’ that he always will be, to all the 29th Division, who knew and appreciated him so well; he will never be forgotten. ”

Like all soldiers Capt. Armstrong was always mindful of home. While in Gallipoli he sent home, monthly letters written in diary format on a daily basis and to his father, Marcus Beresford, in Moyaliffe House, Beach nuts and Gallipoli Oak nuts, which his father successfully later cultivated. These trees are still growing at his former home today. Four of his cigarettes and a cigarette holder bearing the tag “The Simon Arts Store, Port Said,” owned by “Pat” together with many other items from his military career are currently housed in St. Mary’s War Museum here in Thurles, Co.Tipperary, as part of the valuable Armstrong Collection.

“Pats” Memorial Reference is V. F. 18. in Fambourg d’Amiens Cemetery which is in the western part of the town of Arras in the Boulevard du General de Gaulle, near the Citadel, approximately 2 Kms due west of the railway station..

Admiral Sir Sackville Hamilton Carden KCMG (1857 – 1930)

Admiral Sir Sackville Hamilton Carden KCMG was a British admiral who, in cooperation with the French Navy, commanded British naval forces in the Mediterranean Sea during World War I. The title of KCMG or Knight Commander of Saint Michael and Saint George, (Motto is Auspicium melioris ævi (Latin for “Token of a better age”) honours individuals who have rendered important services in relation to Commonwealth or foreign nations.

Carden was born in Templemore, County Tipperary, Ireland, the third son of Andrew Carden and Anne Berkeley.

His early career was marked by service in Egypt and the Sudan, and later, under Harry Rawson in the Benin expedition of 1897. Two years later, he was promoted to captain, and in 1908 to rear admiral. After two years on half-pay, he was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet, and raised his flag aboard HMS London for one year. Following his return to London, he was posted to the Admiralty until August 1912, at which point he was appointed superintendent of the Malta dockyard.

On 26th December 1914, Britain’s War Council discussed the possibility of attacking Turkey in order to re-open the Dardanelles Straits. It was argued that if the operation was successful it would encourage some of the neutral Balkan states to join the Allies.

Admiral Carden proposed a three-stage operation: the bombardment of the Turkish forts protecting the Dardanelles, the clearing of the minefields and then the invasion fleet travelling up the Straits, through the Sea of Marmara to Constantinople. Carden argued that to be successful the operation would need 12 battleships, 3 battle-cruisers, 3 light cruisers, 16 destroyers, six submarines, 4 sea-planes and 12 minesweepers. Lord Kitchener, the War Minister and Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, liked the plan, and on their advice, Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, agreed for the operation to proceed.

It was hoped that the navy would force a way through the Dardanelles on its own. However, it was decided to send British troops and units of the Australian and New Zealand Corps (ANZAC) led by General William Birdwood to the Greek island of Lemnos in case they were needed to take part in the operation.

On 19th February, 1915, Admiral Carden began his attack on the Dardanelles forts. The assault started with a long range bombardment followed by heavy fire at closer range. As a result of the bombardment the outer forts were abandoned by the Turks. The minesweepers were brought forward and managed to penetrate six miles inside the straits and clear the area of mines.

Further advance up into the straits was now impossible. The Turkish forts were too far away to be silenced by the Allied ships. The minesweepers were sent forward to clear the next section but they were forced to retreat when they came under heavy fire from the Turkish batteries.

Winston Churchill became impatient about the slow progress that Carden was making and demanded to know when the third stage of the plan was to begin. Admiral Carden found the strain of making this decision extremely stressful and began to have difficulty sleeping. On 15th March, Carden’s doctor reported that the commander was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Carden was sent home and replaced by Vice-Admiral de Robeck, who immediately ordered the Allied fleet to advance up the Dardanelles Straits.

On 18th March eighteen battleships entered the straits. The fleet included Queen Elizabeth, Lord Nelson, Agamemmon, Inflexible, Ocean, Irresistible, Prince George and Majestic from Britain and the Gaulois, Bouvet and Suffren from France. At first they made good progress until the Bouvet struck a mine, heeled over, capsized and disappeared in a cloud of smoke. Soon afterwards two more ships, Irresistible and Ocean hit mines. Most of the men in these two ships were rescued but by the time the Allied fleet retreated, over 700 men had been killed. Overall, three ships had been sunk and three more had been severely damaged.

In Ireland, Anzac Day is quietly remembered by the ex-patriate New Zealand and Australian communities with an evening service in St Ann’s Church, Dawson St, Dublin 2. Anzac Day commemorations are also attended by members of veterans groups and historical societies, including the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, O.N.E.T., the Royal British Legion, UN Veterans, and others.

The Gallipoli Campaign inspired one of the greatest of all anti-war songs, Eric Bogle’s “The Band Played Waltzing Matilda.“ A line from this ballad “They gave me a tin hat and they gave me a gun,” of course is a myth. Steel helmets would have saved many lives, had these invaders really been given them. But they were not general issue until approximately one year later. The hell endured by these soldiers at Suvla Bay gets a mention in Charles O’Neill’s “The Foggy Dew“, which commemorates the events of Easter 1916, here at home in Ireland. “Twas far better to die ’neath an Irish sky,Than at Suvla or Sud el Bar,“

Leave a Reply