Readers Notes: An interesting fact about the author Robert Wilson Lynd (Roibéard Ó Floinn – latter a socialist and Irish nationalist), the Irish novelist, short story writer, poet, and literary critic James Joyce and his wife Nora Barnacle, held their wedding lunch at the Lynd’s home, No 5 Keats Grove, Hampstead, north-west London, after getting married at Hampstead Town Hall on July 4th, 1931.

Robert Lynd, from a nationalist point of view, would famously write: “Then came August 1914 and England began a war for the freedom of small nations by postponing the freedom of the only small nation in Europe, which it was within her power to liberate, with the stroke of a pen.”

“The Man From Thurles”

[Extract from the scarce antiquarian book published in 1912, entitled “Rambles In Ireland”, by author Robert Lynd.]

I met the man from Thurles, in Kilkenny, as I was going up to the station from the Imperial Hotel.

He was old and shuffling, a ragged creature that once was a man and now humped from town to town with a spotted red handkerchief in his hand, gathering the needs of his belly from among those things that we others do not require for our dogs.

He was as hairy and weather-beaten as a sailor, but he was still like a squeezed and shrivelled sailor. His dark hair and beard were as limp as weed. His eyes, which looks like the eyes of a blind man, with the lids falling down on them as if in deadly weariness, might have belonged to one who had been captured by Algerian pirates in his youth and who had lived in dungeons. He was wearing a tattered ‘wideawake’ * a symbol of homelessness and as he walked, he seemed to put his feet down with uncertainty, like a drunken man.

* ‘Wideawake‘: A broad brimmed, felt, countryman’s hat with a low crown, similar to a slouch hat.

I stopped him to ask whether a church set high amongst gravestones by the side of the road was the Black Friary – I think that was the name of the place.

He made me repeat my question and then in a monotonous voice told me – that I could see for myself – that it was a graveyard in there, mumbling something about Protestants and Catholics both being buried in it – “side-by-side,” – he added for the sake of euphony.

Obviously, he had not heard any question or did not know the answer to it. But that did not matter. I really did not care twopence about the Black Friary.

He went on to say that he was a stranger in Kilkenny and (without ever raising his flyblown eyes) that he had only arrived there that day after a walk of 30 miles.

I asked him what part of the country he was from.

“Thurles,” he said, his voice seeming to come from a fuller chest, as he gave the name of the town in two syllables; “did you ever hear tell of Thurles?

I told him I had been there about a year before.

“It would surprise you” he commented “the difference you would find between the people of Thurles and the people belonging to Kilkenny”.

“How was that”, I asked him.

“Well” he replied, “in Thurles and indeed I might say in all parts of County Tipperary, everybody has a welcome for a stranger”. “For instance”, and he pointed a hand half hidden under a long sleeve at me, “you’re a stranger and”, touching his own coat, “I’m a stranger and if this had to be in the County Tipperary and one of us wanting a bed, we would have no trouble in the world, but to go up to the door of the first house and there would be as big welcome before us as if we had to come with a purse of gold”. “But here”, and his voice grew bitter, “they would prosecute you if you would ask them for as much as a sup of water”.

Suddenly his appearance changed; his bold Jekyll collapsed into a whining Hyde.

“Is that a pólisman I see coming”, he asked, laying his trembling fingers on my arm and steadying his eye to look down the road. “If it’s a pólisman he is, you won’t let him come interfering and ask me questions. You wouldn’t let him do that sir. But in the name of almighty God”, he demanded, battering himself into a kind of rhetorical courage, “what would a pólisman want cross-examining the likes of me? Did I ever steal anything, if it was only taking a turnip out of the field? Did I ever – tell him not to interfere with me!“, he quavered; “tell him not to interfere with me”.

I should not have been surprised if he had put his hand into mine for comfort like a frightened child. He held his breath as the policeman, a bold-boned figure in dark green, trod past. Then he let his breath out again. “They’re tyrants, them fellows”, he said “and the lies they would tell on a poor man might be the meaning of getting him a week or maybe a month in jail, and he after doing nothing at all, but only going quietly from place to place. And thieves and robbers running loose that would murder you on the roadside and no one to say a word”.

“Do you mean tinkers” I asked.

“I do not, then,” he said “I mean soldiers – milishymen”.

I asked him to come into a public house for a bottle of stout, but he said that a bottle of stout would make him light in the head. At length, however, he said he would come and have a glass of ale, if I was sure I could keep the police from annoying him. I gave him my promise and we went in.

“What do I mean?” he said, when I bought him back to the militiamen. “This is what I mean. I had a fine blackthorn stick one time”, he called it a “shtick”- “a shtick I had cut from the hedge with mine own hands and seasoned and polished, and varnished till it was the handsomest stick ever you seen. Well, I was walking along the road in this part of the country one day, when who should meet me but two of these milishymen. ‘Give us baccy’, said one of them – that’s what he called tobacco. ‘I have no tobacco’, said I. ‘You lie’, says he, rising his fist, to threaten me. ‘It’s the truth’, said I, putting up my arm to protect myself”.

He cowered behind his arm and shrank as from a blow at the recollection.

‘If you haven’t tobacco you have money’, said in the milishyman. ‘God knows ‘I have neither money nor tobacco’ says I. And with that he made a rush at me and took the stick off me, and threw me into a bed of nettles and began to beat me with it. ‘Would you have my murder on your souls’ said I; but they only laughed and began searching me to see if I had anything worth stealing. There was nothing but only a few crusts of bread I had tied up in a handkerchief and they took them out and pitch them over the hedge. They would have murdered me I tell you, if they hadn’t heard someone coming.

But that scared them, and they set off down the road.

‘Won’t you leave me my stick’, I called after them. ‘Don’t you see I told you the truth and what use could a rotten ould stick be to the likes of you. And one of them shouted back that I should go to hell for my stick, and he threatened me, if I was to say a word about it, he would find me out and beat me till there wouldn’t be a whole bone left in my body.”

The old man half lifted the glass with his withered arm to his lips and half stooped his withered face to the glass. Having drunk, he wiped his mouth on his sleeve.

“Now wouldn’t you feel lonesome”, he whimpered, his lips against his sleeve “after a stick that you would cut and polished yourself and that you had been used to having with you wherever you went? And many’s a good offer I had to sell that stick. But I would as soon have thought of selling an arrum or a leg. I wouldn’t”, – be paused and his imagination took a leap into great sums – “I wouldn’t have taken a shilling itself for it”.

To him a shilling was something considerable. It represented life for two days; he could exist, he told me on sixpence a day, in a place like Kilkenny. Twopence was the price of a bed in straw on the floor, where the rats ran across you, till you dreamed you had fallen in the middle of a fair and that all the beast were trampling over you. Then in the morning there was a penny for tea, a penny for a slice of bacon, a penny for bread, a halfpenny for sugar and a drop of milk, and a half penny for the loan of a can to make the tea in and a share of the fire. If he had bed and breakfast, he said he did not mind about the rest of the day. He never felt hungry as long as he had his cup of tea in the morning. Sunk to the hovels, though he was, he had the rags of a finer past about him.

He used to be the best slaner, he assured me, in the north of Tipperary.

Did I know what slaning was? It meant cutting turf, and he used to be so good a hand at it that he could earn enough by two or three days’ work to keep him the entire week.

“There’s a man I was at school with in Thurles living in this town”, he went on adding proof to proof of his original respectability, “a rich man, and, what’s more a giving man, and you’ll think it a queer thing, but I have only to walk up to the door and ask if he is in to get all I want to eat and drink and money, too, maybe sixpence into my hand and I going away, to put me a bit along the road. But I wouldn’t go near him”.

“Why was that?” I asked him. He made no sign of having heard me.

“If I was to walk up to his door and he is at his dinner,” he went on like a man describing a vision of Paradise, “he would bring me in and sit me down by his side at the table, and I tell you it would be a table for a feast. There would be roast beef or mutton or a shoulder of lamb or maybe a chicken. There would be ham and” – his imagination seemed to pause on the outer edge of its resources – “all a man could eat and he in a dream”.

“And why do you not go to him?” I asked again.

“I wouldn’t”, he said briefly; and then returned to his vision, “every sort of vegetable there would be on the table – potatoes, and turnips,” – he went over their names in a slow catalogue, dwelling on each as though the very words had magic juices for an empty stomach, “and carrots, and cabbage, and peas, and beans, and parsnips, and curlies * and – and all. I tell you none of the hotels in this city could do better.”

* Curlies – Kale.

“But why don’t you go and see him? I persisted.

He shook his head.

“I wouldn’t” he said helplessly.

There was something puzzling about the old man. It may have been merely his timid and indirect spirit. I doubt if he had the heart to beg – at least openly – either from a lifelong acquaintance or from a stranger.

He was going out of the public house without asking me for a penny.

I stopped him however and put a sixpence in his hand to see him over the night. He peered at it for a moment, and slowly took his hat from his head. Raising his sand-blind eyes, he let them dwell on me. He drew in a long breath as though about to deliver an oration. Then straightened himself into a kind of majesty, he said, with the air of a man uttering the supreme benediction: “You’re the best bloody man I’ve met since I left Thurles”. And having paid me the most magnificent compliment in his power, he put on his hat and wobbled in front of me out of the bar.

THE END

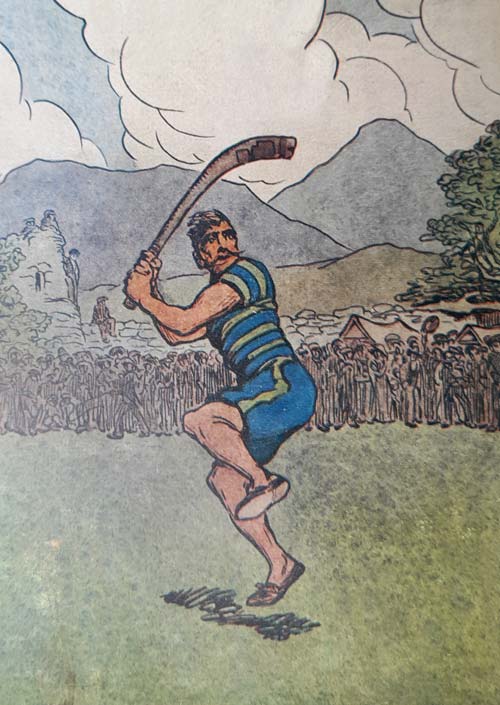

A very enjoyable excerpt….plus, until now I’d never seen that Jack B Yeats illustration of The Hurler…..great stuff!

Glad you enjoyed it Dennis.