In a rare book, [edited with an introduction by Alfred Tresidder Sheppard, (London 1871-1947)], entitled “The Bible in Ireland” (Ireland’s welcome to the stranger or excursions through Ireland in 1844 and 1845 for the purpose of personally investigating the conditions of the poor), written by Asenath Nicholson; we learn of her visit to Thurles, Co. Tipperary and other nearby villages, including Gortnahoe, Urlingford, Cashel, Holycross and Mount Melleray, Co. Waterford.

To follow the story of this remarkable woman – View Part 1 HERE; – View Part 2 HERE, before continuing on this page.

Asenath writes. “I took a car the next morning for Mount Melleray*, a distance of more than 50 English miles.

[Note: * Mount Melleray Abbey is a community of Cistercian (Trappist) monks. The monastery is situated on the slopes of the Knockmealdown mountains, latter a mountain range located on the border of counties Tipperary and Waterford.]

I had hoped to stop at the Rock of Cashel, but was obliged for the present to content myself by seeing its lofty pinnacle. Perched upon the top of a rock, it has stood the ravages of centuries, looking out upon the world, and the City beneath its feet, now going fast to decay.

Cashel looked more deserted this day than usual, as a rich brewer in the city, a brother of Fr. (Theobald) Mathew, (latter teetotalist reformer), had died, and the shops were closed in honour of his funeral.

When travelling by coaches and cars, I have been so much annoyed by the disgusting effluvia of tobacco, that I dread a ‘next stage’, the changing of horses being the signal for a fresh lighting up.

At Cashel I sat behind a rustic* who had reloaded his pipe, and he began puffing till my unlucky head was enveloped in a dense fog, a favourable wind wafting it in that direction.

[* Note: Word ‘rustic’ means a rural dwelling man].

Knowing that the consumers of this commodity are not fastidiously civil, I forbore to complain, until I became sick. At length I venture to say ‘Kind Sir, would you do me the favour to turn your face a little? Your tobacco has made me sick.’ Instantly he took the filthy machine from his mouth and archly looking at me, ‘Maybe yer ladyship would take a blast or two at the pipe,’ resumed his puffing without changing his position. I was cured of asking favours.

I blush for my country when, on every car, and at every party and lodging house, this everlasting blot on America’s boasted history is presented to my eyes. Even the illiterate labourer, who is leaning over his spade, and tells me of his 8 pence a day, when I in pity explain, ‘How can you live? You could be better fed and paid in America,’ often remarks, ‘Aw you have slaves in America, and are they better fed and clothed?

A few hours carried us to Clonmel, a town neat in its appearance, containing about twenty thousand inhabitants, amongst whom are many Quakers.

Here some of the ‘White Quakers’*, a small body of ‘Come-outers’ from the Quakers, formerly resided, but they have removed to Dublin. These people bitterly denounce others, but take liberties themselves, under pretence of walking in the Spirit, which by many would be considered quite indecorous. The men wear white hats, coats and pantaloons of white woollen cloth, and shoes of undressed leather; the women likewise dress in white, to denote purity of life.

Note: * Joshua Jacob (1802–1877), founder of the ‘White Quakers’, was born in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. Educated at Newtown school, Waterford; Joseph Tatham’s school in Leeds and later in Ballitore, Co. Kildare; in 1829, he married Ms Sarah Fayle who bore him three sons.

Mr Jacob established himself as a grocer in Dublin. His shop, known as the “Golden Teapot”, specialised in the sale of different varieties of tea.

By 1838 having publicly criticized the comforts of Quaker life, he was disowned by the Quaker community, and decided to form a society of his own, calling its members ‘White Friends’, ‘Shining Ones’, or, officially, ‘The Universal Community’, latter which gained considerable adherents, briefly in Clonmel, before spreading to other areas on Ireland’s south east.

In 1842, he and his followers began to practise communal holding of all earthly goods, while appearing clothed in loose, unbleached loose-fitting clothes made in calico and linen, and frequently going barefoot; hence their name ‘White Quakers.’The hostility of the orthodox Quaker community towards this practise of the communal holding of all earthly goods, came to a head in late1842, when Mr Jacob’s breakaway community took ownership of an inheritance, valued at £9,000, donated by Mr Jacob’s recently widowed sister-in-law.

He was made the subject of an action, taken before Lord Chancellor, Edward Burtenshaw Sugden, by the executor of the property, and was confined to London’s Marshalsea debtors prison, from January 10th 1843 following his refusal to recognise the court.

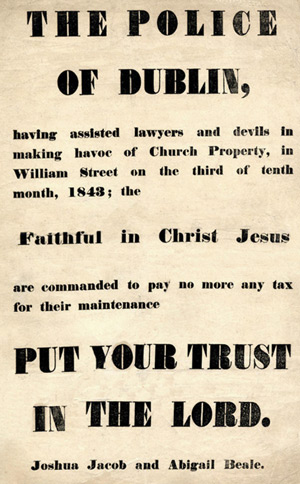

Having sold his shop, he sent instructions to the ‘White Quaker’ community from his prison cell situated, just south of the River Thames; firing broadsides in the shape of printed pamphlets, at society as a whole, each composed with the assistance of Ms Abigail Beale, who took up residence with him in Marshalsea prison.

His rejection of the final judgment of the court, resulted in the community’s property being seized and put up for auction, hence his opposition to paying taxes supporting British police. [See image above.]

Mr Jacob was release from prison in 1846, on grounds of ill health. The ‘White Quakers’ remained active in early food distribution during the Great Famine period 1845-1848, before disintegrating as a society in the latter end of the same year.From 1842 Mr Jacob had lived apart from his wife, who no longer shared his religious views. Later on her death, he married Ms Catherine Devine, adopting her Roman Catholic religion, before raising six children in that faith.

In 1849, Mr Jacob established a new community at Newlands, Clondalkin, Co. Dublin. Here also this newly formed community slowly disintegrated.

Mr Jacob passed away in Wales on February 15th, 1877; before being repatriated and interned in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, in a plot of ground, previously purchased for ‘White Quakers.’

A Roman Catholic priest soon seated himself upon the car, whom I found polite and intelligent. His first enquiries were concerning American slavery. Its principles and practices he abhorred, and he could not comprehend its existence in a Republican government.

Seeing a labourer digging a ditch under a wall, I asked him the price of his day’s work. ‘A shilling ma’am.’ ‘This is better than in Tipperary, sir.’ ‘But we don’t have this but a little part of the year; the Quakers are very hard upon us here, ma’am; giving us work but a little time, and if a poor Irish man is found to be a little comfortable, they say “he has been robbing us.” ‘The English, too, are expecting a war and they want us to enlist, but the divil of an Irishman will they get to fight their battles. O’Connell is not out of prison’ *, and stopping suddenly leaning on his spade, ‘How kind America has been to us; we ought to be friends to her, and the Irish do love her.’

He grew quite enthusiastic on America’s kindness and Britain’s tyranny, dropped his spade, climbed the wall, where I was standing, and expiated on Ireland’s woes and America’s kindness, till I was obliged to say ‘good-bye.’

[Note: * In 1844, the year Asenath had arrived in Ireland, Daniel O’Connell was arrested and prosecuted for conspiracy, following seditious speeches made by O’Connell and others; latter namely his son John O’Connell, Thomas Steele, Charles Gavan Duffy, Richard Barrett, John Gray, and T.M. Ray, during monster meetings in locations; e.g. Clontarf, Co. Dublin, Hill of Tara, Co. Meath and Thurles, Co. Tipperary.

O’Connell’s trial began in the Four Courts in Dublin on January 15th 1844. Roman Catholics were excluded from the jury, with the Crown also refusing to supply the accused, with a list of witnesses.

Then aged 69 and despite being in bad health, Daniel O’Connell and his fellow accused were found guilty, but were allowed to choose their own place of incarceration.

They chose the Richmond Bridewell, latter a prison mainly used to accommodate debtors, located on Dublin’s South Circular Road.

The Young Ireland leaders, William Smith O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher, were held there four years later, in 1848, following their arrest after the battle of ‘The Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch’ in 1848 in Ballingarry (SR), Thurles, Co. Tipperary.

However, same accused actually served out their sentences in the comfort of the private quarters of the prison’s Governor and Deputy-Governor, rather than in their chosen prison. They were allowed to employ servants and family members could stay with them also. A steady stream of gifts and guests flowed into the prison and according to Charles Gavan Duffy, the dinner-table was never set for less than thirty persons. Their incarceration would become known as ‘The Richmond picnic’. Indeed one of the O’Connell detainees wrote that their imprisonment proved as unpleasant as ‘a holiday in a country house.’]

O’Connell and the other prisoners incarcerated with him, were freed on September 6th of the same year, 1844, after the British House of Lords overturned their convictions. However, they returned to Richmond prison the next day, so that a ceremonial release could be stage managed. O’Connell would now leave the prison aboard a special triumphal chariot, latter drawn by six grey horses, with 200,000 people lining the streets to cheer.

Asenath continues to write: “A new car and driver were now provided. These drivers are a terrible annoyance, with their ‘Rent ma’am.’ ‘Rent! for what?’ For the driver ma’am.’ ‘I will give you an order on Bianconi, sir.’

I had been told that Bianconi paid his coach men well, and forbade they’re annoying the passengers, but afterwards found that they received from him but 10 pence or a shilling (12 pence) a day, out of which they must board themselves. I was sorry I spoke so to the driver, and hope to learn better manners in future.

Our route lay now through the files (‘Files’ in this context meaning ‘one behind another’) in the intricate windings of the Knockmealdown mountains, and had my faith been strong in giants, fairies, and hobgoblins; the dark recesses and caves in these mountains would have afforded ample food for imagination.

In the coming days read about Asenath Hatch-Nicholson’s visit to Mount Melleray Abbey [Part4] from Thurles.

Leave a Reply