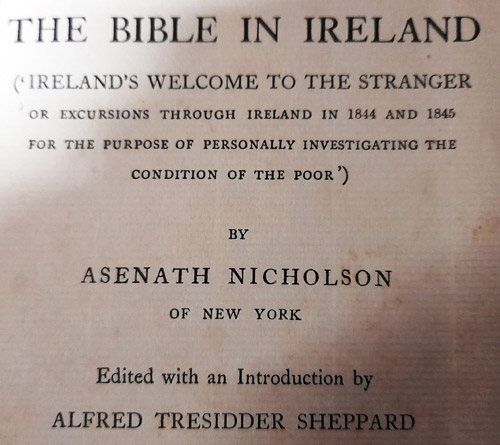

In a rare book, [edited with an introduction by Alfred Tresidder Sheppard, (London 1871-1947)], entitled “The Bible in Ireland” (Ireland’s welcome to the stranger or excursions through Ireland in 1844 and 1845 for the purpose of personally investigating the conditions of the poor), written by Asenath Nicholson; we learn of her visit to Thurles, Co. Tipperary and other nearby villages, including Gortnahoe, Urlingford, Cashel and Holycross.

See Part 1 of her story Here

Asenath Nicholson writes: “The celebrated estate of Kilcooley, (Gortnahoe, Thurles, Co. Tipperary) has descended by hereditary title, from the days of Cromwell, till it is now lodged in the hands of one who shares largely in the affections of all his tenants, especially the poor.

The wall surrounding his domain is said to be 3 miles in extent, including a park containing upwards of 300 deer and a wild spot for rabbits. A church and an ancient ivory covered Abbey, of the most venerable appearance, adorn part of it.

But the pleasure of walking over those delightful fields is enhanced by the knowledge that his tenants are made so happy by his kindness.

To every widow he gives a pension of £12 a year and to every person injuring himself in his employment, the same sum yearly, as long as the injury lasts.

His mother was all kindness, and her dying injunction to him was ‘to be good to the poor’. His house has been burnt*, leaving nothing but the spacious wings uninjured. An elegant library was lost.”

Note on ‘Burnt’ *. A huge accidental fire partly destroyed the property, causing it having to be reconstructed in the 1840s, during which the family occupied the old abbey. The interior today mostly dates from after that fire.

His mother, whom he ardently loved, was buried on the premises and his grief at her death was such that he left the domain for 12-months.

He supports a dispensary for the poor, who resort to it twice a week, and receives medicine from a physician who is paid some £60 a year for his attendance. I was introduced to the family of this physician, to see his daughter, who had been a resident in New York some 6 years, and hoped soon to return thither to her husband and child, still living there.

As I was seated a little son of 2 years old, and born in America stood near me. I asked his name. Yankee Doodle, ma’am was the prompt reply. This unexpected answer brought my country, with every national, as well as social feeling, to mind, and I classed the sweet boy in my arms.

Let not the reader laugh; he may yet be a stranger in a foreign land. This name the child gave himself, and insists upon retaining it. O! those dear little children! I hear their sweet voices still: ‘God bless ye, lady, welcome to our country,’ can never be forgotten.

While in this family, I attended the Protestant church on Mr Barker’s domain* and heard the curate read his prayers to a handful of parishioners, mostly youths and children. By the assistants of a rich uncle of his wife’s, he can ride to church in a splendid carriage, which makes him tower quite above his little flock. His salary is £75 per annum.”

[Note on ‘Mr Barker’s domain’ *. Prior to 1770 the Barkers may not have spent much time at Kilcooley and when they were present, they lived in the old abbey, which had been modified to serve as a private residence. Without any direct heir provided by the last Sir William Barker in 1818, and following his death, his estate was inherited by his nephew, Chambre Brabazon Ponsonby, on condition he adopted the surname, ‘Barker.’ He in turn passed away in 1834 and the Kilcooley estate then passed to his eldest son, William Ponsonby-Barker of whom Asenath Nicholson speaks.

Latter William referred, was himself an ardent Evangelical Christian and in the years prior to his death in 1877, he would habitually follow the example set by King David (c.1005–965 BCE), and Abishag, latter a native of the town of Shunem north of Mt. Gilboa in ancient Palestine, (See 1 Kings 1:1-4), originally brought to King David’s bed to “lie in his bosom”, chastely, to keep him warm as he neared death according to the Old Testament.

As stated, the ageing William Ponsonby-Barker would also take a young woman to bed with him, as a human hot water bottle. It is said that be choose from among the housemaids, who were lined up following evening prayers.

The story has been repeated down through the years, possibly repeated because on one occasion, the maid whom he selected, offended his sense of smell, so in the darkness he sprinkled her liberally from a bottle containing what he believed contained perfumed water. The following morning it was discovered that the bottle actually contained ink.]

Asenath Nicholson Continues: “Thurles, an ancient town in the County of Tipperary contains a good market house, fine chapel, college for Catholics, nunnery and charity school, with a Protestant church and Methodist chapel.

I took a ride of 3 miles to visit Holy Cross, (Thurles, Co. Tipperary). On our way we passed a splendid estate, now owned by a gentleman who came into possession suddenly by the death of the former owner from whom he acted as agent. Last Christmas they had been walking over the premises in company; on their return the owner met with a fall and was carried home to die in a few hours. It was found he had willed his great estate to his agent.

Holy Cross was the most vulnerable curiosity I had yet seen in all Ireland. We ascended the winding steps and looked forth upon the surrounding country, and the view told well for the taste of O’Brien, who reared this vast pile in 1076. (Today there are few remains of the original 12th/13th century church; only the north arcade of the nave and parts of the south aisle date from this time.)

The fort containing the chapel is built in the form of a cross. The architecture, the ornamental work, and the roofs of all the rooms, displayed skill and taste. We visited the apartments for the monks; the kitchen where their vegetable food was prepared, and the place where repose so many of their dead. Pieces of skulls and leg bones lay among the dust, which had lately been shoveled up and as I gathered a handful and gave them to an old woman, who acted as my guide, she said, ‘This cannot be helped. I pick ‘em up and hide ‘em, when I see ‘em, and that’s all can be done; people will bury here, and it’s been buried over for years, because you see ma’am, it’s the place of saints. People are brought many miles to be put here the priest from all parts have been buried here, and here is the place to wake them,’ showing a place where the coffin or rather body was placed in a fixture of curiously wrought stone.

The altars, though defaced, were not demolished; the basins cut out of the stone for the holy water were still entire; and though many a deformity had been made by breaking off pieces as sacred relics, enough remains to show the traveller what was the grandeur of the Romish Church in Ireland’s early history.

I stayed in Thurles with a Catholic family, and the husband endeavoured to induce me to become one church; but zeal was tempered with the greatest kindness.”

Over the coming days – “Visit To Thurles Co. Tipperary By Asenath Nicholson. [Part 3],”

Leave a Reply