Cork born, John Francis Whelan [1900 -1991] possibly better known by all as Sean O’Faolain was one of the most influential figures in 20th-century Irish culture. A short-story writer of international repute; he was also a leading commentator and critic.

In his book “An Irish Journey” (from the Liffey to the Lee), latter published first in 1940, (Published in America in 1943), he reflects on his visit to Liberty Square, here in Thurles, Co. Tipperary.

For those who may have missed Part 1 of his story regarding his sojourn in Thurles, Co. Tipperary; same can be read HERE

______________________________________________________________

PART 2 – (Final part continues) – Sean O’Faolain writes as follows,

“The old man on the bridge remembered all the famous people I associate with Thurles, such as the famous Archbishop Croke, Smith O’Brien and the Fenians, Parnell, John Dillon and especially William O’Brien, that fiery particle from Cork who with Tim Healy was the most gallant and the wildest fighter of the Irish parliamentary party and who alone continued the best traditions (as well as some of the worst) of that party into the modern Sinn Fein revival.

He showed me where the old Market House used to stand in the square with its little tower and it’s frontal terrace, stepped at each side and he talks so well I could see the vast political meetings there, of nights, with the tar-barrels smoking and spluttering in the wind, their flames leaping in the reflecting windows about, the police lined along the opposite walls or grouped in side streets, fingering their carbines or batons in case there should be a clash between rival parties.

The great Archbishop would stand there tall and impressive; with him another big clerical figure – with apparently much more suave and evasive, Canon Cantwell; Dillon slightly stooped; O’Brien bearded like a prophet and Parnell ready to tear the hearts of the crowd with some clinching phrase.

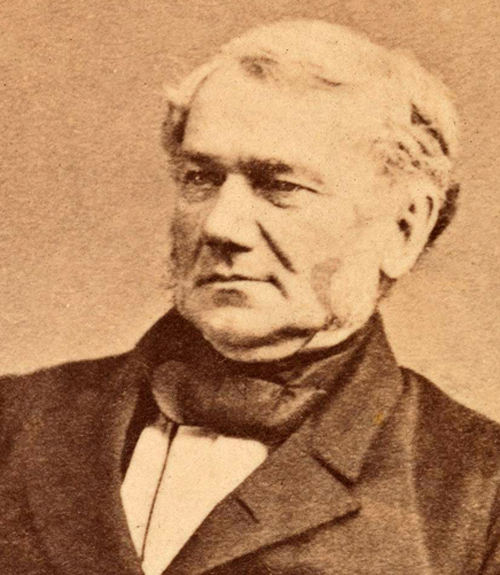

Later, I looked up at Croke’s fine statue in the square and went to the Cathedral (Cathedral of the Assumption, Thurles), to see his bust in its niche – a square jawed firm mouthed man, much what one would expect from his life story, all solid and all of a piece. He was one of the last great nationalist prelates, for the Parnell split struck a deadly blow at a priest in politics, and though the hierarchy has manfully stood by the people several times since then, especially during the Revolution, they almost always act in cautious and deliberate concert and the freelance fighting Bishop has since died out.

There is something fabular (having the form of a fable or story) about Croke. He destroyed all his papers after reading Purcell’s “Life of Cardinal Manning“ and little positive remains.

It is said that he fought at the barricades in Paris in the revolutionary troubles of 1848, [“Springtime of the Peoples”]. One can, after looking at his portraits and reading his life, well believe William O’Brien who vouches for it; see the young priest of twenty-four caught by the excitement of the times, the rattle of Cavignac’s musketry, the flutter of the Red flag, the barricades of furniture, carts, wagons, dead horses, the cries of the demagogues.

There is another like story which maintains that when he was a student either in Paris or in that pleasant college of the little Rue de Irlandais, behind the Pantheon orat Menin, he horrified a class by denying in a syllogism, (Latter a form of reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn from two given or assumed propositions), was expelled, put his pack on his back and tramped across Europe to the Irish college at Rome and was admitted there. (The rector was John Paul Cullen, later Cardinal, a friend of Pope Leo, one of the most influential men in the whole European church, the man who defined for the Catholic world the precise formula of Papal Infallibility.)

I should like to believe the stories, they are such an excellent prologue to a life during which, as curate, professor, college president at Fermoy, chancellor, parish priest, bishop in New Zealand, archbishop of Cashel, he was in every station, the most outspoken, forward driving, irrepressible, warm-hearted, affectable, and sympathetic figure, in the entire history of the Irish episcopacy.

When he was appointed Bishop, it is said that the appointment was most unpopular in his diocese and if I made believe my old man at the bridge, (Barry’s Bridge Thurles), who kept on remembering local lore about him – on his first Sunday he got up in the pulpit and told the people that he knew it, that he now had the post and that he “was, thank God, under no compliment to the priests and people of Tipperary for it”.

He gave dinner in celebration of his appointment. Only one of his opponent’s dared to stay away, a professor in the Diocesan Seminary, father Dan Ryan. The murmur went round the table before the meal ended that Ryan had been suspended, an unheard of punishment for what was merely a social gaffe. But it was true. Croke had suspended him for twenty-four hours, “just to show him who was the boss”.

He was as generous as he was stern. In the great days of the Irish parliamentary party, William (Smith) O’Brien used to stay at the Palace. One night, after O’Brien had gone to bed the Archbishop paused outside his door and for some idle reason apparently looked at O’Brien’s boots. They were in tatters. He sent out into the town early next morning for a new pair of boots. O’Brien soon afterwards received the cheque for €200.

Those must have been great days and nights in that Palace in Thurles and Croke has always seemed to me an epitome (perfect example) of the Irish priest at his best, sitting there among the Irish political leaders of the day Biggar, Davitt, Parnell, O’Brien and the rest. Outside are the Tipperary farmers and their wives, down from the rich hills, up from the Golden Vale. The great square is dense with chaffers and bargainers by day; by night with crowds waiting to hear him. It is splendid to see his statue today in that same square (Liberty Square, Thurles) with the market surging around it, like a navy moored to his pedestal.

And he was no mere political priest. At the Parnell divorce he took Parnell’s bust, which he had in his hall, and kicked it out of the door, he was heartbroken. “Ireland” he moaned “is no fitting place for any decent man today. The warmth that used to gladden my heart has disappeared. There is nothing to cheer me in church or state”.

He wished even to fly from Thurles and Tipperary and Ireland, back to New Zealand.

I naturally have a warm corner for Croke; he was a Cork man and they say he never lost his Cork accent and even to the end of his days, ordered his food and other needs from Cork city, rather than give Tipperary, which had not wanted him, the benefit of his custom. A curious thing is that his mother was a Protestant. She remained a Protestant to within a few years, I think only four, of her death.

History, as all over Ireland, is an odd medley in the popular mind of this modern Tipperary – if one may judge by its chance projections in Thurles. They have, for example, lost their old market hall, with its many associations. The one castle which remains is only part of what once stood there.

There were once seven castles in Thurles. In the backyards any good antiquary, like, I imagine, the local Archdeacon Seymour or Dr Callanan, could point you out the remains of the old walls in the town’s backyards. On the other hand on the wall of Hayes hotel there is a neat plaque to commemorate the founding there, of the Gaelic Athletic Association in 1884, with Croke as the first patron. While the modern Gaelic revival having permitted the castles to disappear, records a group of new terrace houses beyond Kickham Street, heroes and heroines nobody can possibly visualise or know anything about – Oisin Terrace, Oscar Terrace, Dalcassian Terrace, Emer Terrace, Banba Terrace and so on.

It is a typical experience of the confused and ambiguous, mingled nature of this modern Ireland to go from that end of the town to the other, to the great Beet Factory, pulsing and hammering away inside its impressive buildings, with its rows and rows of railway sidings and it’s rows and rows of windows shining at night across the Tipperary fields”.

Story Ends

GREAT HISTORY

LOVE THE HISTORY . SADDENED THAT SO MUCH OF OUR LOCAL HISTORY IS BEING LOST AND NOT TAUGHT IN THE LOCAL SCHOOLS.