Spare a moment today to remember Corporal John Cunningham VC, who died 103 years ago today, April 16th 1917.

Corporal John Cunningham (8916), was born in Hall Street, Thurles Co. Tipperary, on the 22nd October 1890; one of two sons of Johanna (Smith) and Joseph Cunningham. He joined the 2nd Battalion, Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment during the First World War. Please visit HERE for further information.

Corporal Cunningham was an Irish recipient of the Victoria Cross, latter the highest and most prestigious award granted for gallantry in the face of the enemy, that can be awarded to any member of British and Commonwealth forces. He died on this date which fell on a Monday, April 16th 1917, aged in his 27th year.

The Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment was nicknamed, ‘The Royal Canadians’, owing to the amalgamation of the 100th Regiment of Foot (Prince of Wales’s Royal Canadian) and the 109th Regiment of Foot (Bombay Infantry), which formed its home depot 55 km from Thurles, in Crinkill Barracks, Birr, Co. Offaly.

For the record, some 6,000 Irish recruits would enlist at Crinkill Barracks, Birr, during the First World War. Indeed, an airfield was later built there in 1917.

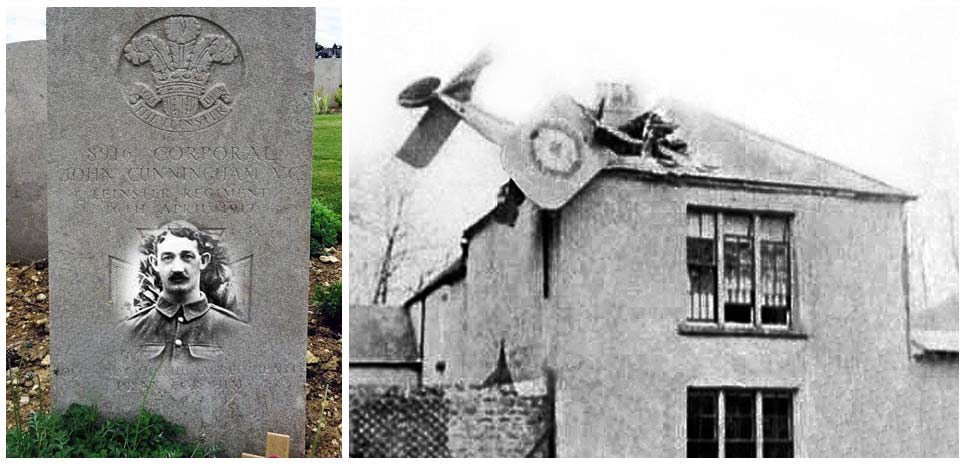

It was here that Flight-Lt. William Edgerton Taylor (Pilot) and Sergeant Thomas William Allan (Passenger) were both killed, when the leading edge of the tail wing on their biplane, clipped a tree, forcing it to crash through the roof of Crinkill House, Birr on March 28th 1919.

The pilot, we understand, was giving an exhibition of aircraft “nose-diving”.

Picture Right: Crashed biplane in roof of Crinkill House, Birr, Co. Offaly.

Corporal Cunningham was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously, following his actions on April 12th 1917, at Bois-en-Hache, near Barlin, France. He died as a result of his injuries four days later, April 16th 1917, and is buried in Barlin cemetery, Pas de Calais, France, 103 years beside 1116 other casualties, in Plot 1, Row A, Grave 39.

Perhaps this outstanding bravery carried out by Corporal Cunningham on that same fateful Thursday in April 1917, may have been influenced by the loss of his brother Corporal Patrick Cunningham, also a member of the Leinster Regiment, who tragically lost his life some 22 months earlier, on Friday June 4th 1915, at the tender age of just 20 years.

Barlin is a village about 11 Kms south-west of Bethune on the D188, between the Bethune-Arras and Bethune-St. Pol roads, about 6.5 Kms south-east of Bruay. The Communal Cemetery and Extension lie to the north of the village on the D171 road to Houchin.

On June 8th 1917, The London Gazette, latter the oldest surviving English newspaper and the oldest continuously published newspaper in the UK, reported the following article regarding the reported actions of Corporal John Cunningham: –

Corporal John Cunningham (8916) – Citation

“For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty when in command of a Lewis Gun section on the most exposed flank of the attack. His section came under heavy enfilade fire and suffered severely. Although wounded he succeeded almost alone in reaching his objective with his gun, which he got into action in spite of much opposition. When counter-attacked by a party of twenty of the enemy he exhausted his ammunition against them, then, standing in full view, he commenced throwing bombs. He was wounded again, and fell, but picked himself up and continued to fight single-handed with the enemy, until his bombs were exhausted. He then made his way back to our lines with a fractured arm and other wounds.

There is little doubt that the superb courage of this N.C.O (non-commissioned officer) cleared up a most critical situation on the left flank of the attack. Corporal Cunningham died in hospital from the effects of his wounds.

The London Gazette, 8th June 1917

His Victoria Cross was presented personally to his mother, Johanna, on July 21st 1917, by King George V, at Buckingham Palace, London, England.

Johanna Cunningham’s Story

To close neighbours, Mrs Johanna Cunningham later confided the story of her return to Thurles after her meeting with King George V, at Buckingham Palace.

She had kept her initial invitation to Buckingham Palace, for the most part, secret. Now on her return journey; not familiar with travelling far from her native home, she was anxious not to miss the platform at Thurles Railway station, as she travelled on the mail train from Dublin. As she entered each railway station on the route, she could clearly identify the station names on the large cast iron signs.

On reaching Thurles station as the steam train reduced speed, she checked through the window to confirm her whereabouts. She took note of a red carpet being rolled out on the platform and above the sound of the engine a small brass band was beginning to play music.

She was angry with those who may have broken her confidence regarding her meeting with King George V. and the presentation of the VC medal. She was aware from other instances, that relatives of fighting men known to be attached to the British Army, were being shunned, beaten and otherwise ostracised by an IRA / Sinn Féin membership.

In a panic she dropped down between the railway seats, believing that both the red carpet and band were there to welcome her home. After delivering its other passengers the train moved on to the next station; with a frightened and angry Johanna Cunningham on board. Having alighted at Gouldscross station platform, she took another train back to a now less busy Thurles railway station platform.

As it later emerged, the feared red carpet and brass band were there to welcome a travelling politician. Her secret trip to London and her rubbing of shoulders with royalty, would remain safe from the Thurles community for a while longer.

The Victoria Cross

The bronze metal from which all Victoria Crosses are made, is cut from cannons captured from the Russians at the seige of Sebastopol, during the Crimean War and is supplied by the Central Ordnance Depot in Donnington, Berkshire, England.

Corporal John Cunningham’s medal today exists, on loan by his relatives at the Imperial War Museum, Lambeth Road, Kennington, London, England.

“At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.”

[Extract from poem “For the Fallen”, by Robert Laurence Binyon (1869-1943).]

This is my great uncle and I’m so proud of him.

We used to play with the medal which was on my Nana’s sideboard. Little did we know then what he did, and hopefully it’s never allowed to be sold.

Does anyone know what happened to John’s service medals which should have been kept with the VC?

The Victoria Cross medal is now in the Imperial War Museum in London, in the Lord Ashcroft Gallery. Lord Ashcroft collected Victoria and George Crosses and paid for the dedicated museum within a museum. The medal was on loan, but I noticed it had been bought by Lord Ashcroft recently. It is an excellent display and in a place that it will be appreciated, as is his grave in France, which is well attended, but a shame the medal is both out of Ireland and has been sold. I don’t know what happened to John’s service medals or Patrick’s WW1 medals. My father-in-law, Freddie Cunningham, is John’s nephew, via his younger brother Joseph.

If you ever get a chance during any future visit, please take a picture of the display, we would love to see it.

George, I just send you a letter on your contact site.But a message has come back to say it did not go out. If you receive it George can you please let me know. Thanks. Katie.

Hi Katie,

Got nothing Katie except what you currently published this morning at 5:13am (Irish time).

[ i.e. I just sent you a letter on your contact site.But a message has come back to say it did not go out, If you receive it George can you please let me know. Thanks. Katie.]

A private email sent by me to you stated ” Message blocked

Your message to bigpond.com has been blocked. See technical details below for more information”.

Hi Susannah Trying to get in contact with you. I have given George Willoughby my email address if you could email me.

Regards

Marie Edwards