A secret ‘briefing note’, now released as part of the 1988 Irish State Archive 30-year rule, (Period for which Irish confidential government documents are restricted from public viewing by taxpayers), sheds new light on the non-extradition to Britain of a Tipperary born Irish Roman Catholic priest, accused by British intelligence of being an IRA volunteer.

This refused extradition to Britain was to spark an angry stand-off between the then Irish government led by An Taoiseach Mr Charles J. (C.J.) Haughey and the British government, then led by the now Late Mrs Margaret (Maggie) Thatcher.

Fr. Patrick (Paddy) Ryan.

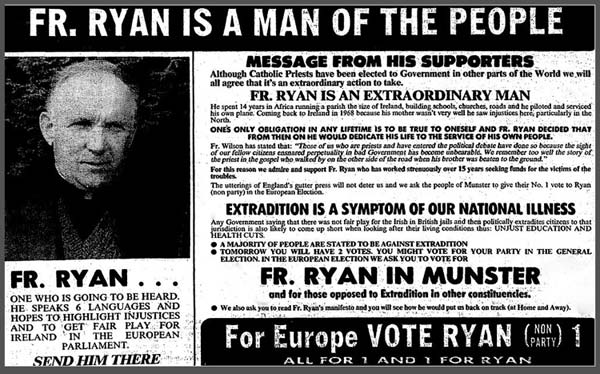

Fr. Ryan contested the European Parliamentary Elections in 1989, as a Sinn Féin supported Independent, however, he failed to be elected, but received over 30,000 votes.

The priest in question was Fr. Patrick (Paddy) Ryan, born on June 26th, 1930, in Rossmore, Cashel, Co. Tipperary, and one of six children born to a rural farming family.

Paddy Ryan attended the local Christian Brothers School (CBS) here in Thurles and later the Pallottine College, Thurles, going on to train in the priesthood at St. Patrick’s College, Thurles, before being ordained on June 6th, 1954.

As a member of the Pallottine Order, he went to work on the missions in the diocese of Mbulu, one of the six districts of the Manyara Region of Tanzania and then later in America and later still in the city of London.

Fr. Ryan had shown no great interest in politics beyond a hatred for past and present British rule on the island of Ireland, however the Catholic Church and the Pallottine Order would formally suspend him from priestly duties after he refused a transfer to a parish church in England. Later during a trip to Rome in the summer of that year, he is reported to have informed Italian priests that he hoped that the IRA would bomb the centre of London.

By the Autumn of 1973, he was shuttling back and forth between Dublin and Geneva, opening bank accounts and transferring funding (over £1,000,000) reportedly granted by his newly acquired contacts within Libyan Military Intelligence in Tripoli.

By 1974, Fr. Ryan had set up a base in Le Havre, in northern France’s Normandy region, staying in a local tourist hotel while working to set up new IRA supply lines. Bank accounts were put in place all over Europe in the names of different individuals, particularly in Luxemburg and Switzerland. Couriers were located in Brussels and Paris, while agents were identified and sanctioned to operate on cross-channel ferries. Lorry drivers covering the routes between Dublin and the Continent, also made themselves available to assist him in his IRA activities. Pistols and ammunition continued to be supplied concealed in the doors of these lorries and nitro-glycerine was being smuggled in containers of Italian lemons.

Memopark Swiss Timer.

It was understood that Fr. Patrick Ryan was the first to recognise the future use for the Memopark Swiss timer, latter a gadget used by motorists. You pay the metre to park your car, then set the dial on your Memopark. It rings in your pocket when your parking meter expires. But a metal arm now positioned to the top of this apparently harmless Memopark timer and same can act as a perfect bomb timer.

In May of 1975, Fr. Ryan is believed to have found a novelty shop in Zürich Switzerland, which sold this simplest of gadgets and bought out their entire stock of 400, which were then converted to complete electrical circuits on explosive devices. Over the next 18 months, these converted Memopark Swiss timers were found at the scene of 185 different explosions in Northern Ireland and also at a located bomb factory site in London.

Intervention by Scotland Yard, & Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6.

It was not England’s Scotland Yard or MI6, who first tumbled to Fr. Ryan’s IRA activities; rather a Canadian tourist who was lodged in the next room to him in his Le Havre hotel. This same tourist could overhear his neighbour tuning in to short-wave radio every morning as if he was trying to locate a signal, and he noticed Fr. Ryan regularly to be found in the dockland area; seeking information on cargo vessels travelling to Ireland. The hotel staff when questioned, would inform the Canadian that Mr Patrick Ryan was a seaman, however the Canadian tourist wondered how a lowly sailor could afford the expense of dozens of international weekly phone calls.

Some days later, Fr. Ryan checked out of the hotel and the Canadian gained access to his room, seizing the contents of Fr. Ryan’s waste paper basket. The following day the Canadian took on a ferry to Southampton, England. Hampshire Special Branch Force now researched this binned waste paper proffered to them, noting same contained phone numbers of known IRA contacts in Dublin and Europe and a the previously unknown address of a council flat in east London, owned by a female named Catherine, who worked with mentally handicapped children, and who had fallen head-over-heels in love with a charming priest. Under his guidance Catherine would now be often used (possibly unknown to herself) as an IRA money courier, believing she was delivering funding which would be eventually later used to build them both a future home together.

It was during ongoing surveillance by French police, latter reporting to Scotland Yard, that an British MI6 undercover team watched Ryan built his vast connections. Under cover, they watched in January 1975, as IRA veteran Joe Cahill and Eamonn Docherty, latter Assistant IRA Chief of Staff, travelled to Le Havre to meet with Fr. Ryan. They would follow the three men as they journeyed to Paris to meet a notorious arms dealer, known as ‘Max’.

Later, while on the run, Fr. Ryan was continuously arrested and released all over Europe. Arrested in France in December 1976; then in February 1977 it was Italy and in March of that same year it was Luxembourg; however England were never able to beat Europe’s extradition laws to get him returned to London for trial.

It was around 10.40am on July 20th 1982, when a nail bomb exploded in the boot of a blue Morris Marina, latter parked on South Carriage Drive in Hyde Park, as soldiers of Queen Elizabeth II’s official bodyguard regiment (Household Cavalry), were passing. Four soldiers and seven horses were killed. [A survivor, Michael Pedersen, later suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder; after splitting from his wife he committed suicide in September 2012, but not before killing two of his own children.]

Police forensic officers found the remains of a sophisticated electronic switch had been used to detonate the device using a radio signal. This switch became a vital clue to police in their efforts to find those responsible. In tracing its history, their search would end in Paris, where an informer admitted to knowing the switch’s history and disclosed the name of the purchaser of this device as the Provisional IRA’s “bomber priest”, Fr. Patrick Ryan.

Here now this informer would identify a 58-year-old Irish Roman Catholic missionary; not as just a Church fund-raiser; but a launderer of massive IRA funding, who is extremely skilful at manipulating a network of hidden bank accounts, and a man who had succeeded in forging strong links between the Irish Republican Army and the Libyan revolutionary leader Colonel Muammar Ghadaffi, [Latter, himself, who would end up possibly stabbed to death or shot in October 2011, before being placed in a local market freezer unit, before being publicly displayed for four days.].

Fr. Ryan would later be sought for questioning in connection with the murders of three off-duty RAF British servicemen in the Netherlands on May 1st, 1988. Ian Shinner, from Cheshire, stationed at RAF Wildenrath was shot dead, while seated in a car in Roermond city, close to the German border, at around 1.00am. Two other men, both Scottish, died when a bomb was placed under their car outside a disco in Nieuw-Bergen, Holland, about 30 miles north of Roermond in the south-eastern part of the Netherlands. The service men were later identified as 22-year-old John Millar Reid, latter a native of Lenzie situated in the East Dunbartonshire council area of Scotland, and John Baxter, a 21-year-old, from Glasgow city.

The IRA were quick to issue a statement from Belfast saying: “We have a simple message for Thatcher (latter then the British Prime Minister). Disengage from Ireland and there will be peace. If not, there will be no safe haven for your military personnel and you will regularly be at airports awaiting your dead.” British and Irish governments were both equally quick to condemn these attacks.

Irish Republicans on the other hand saw these attacks in the Netherlands as the ultimate revenge for the killing, two months previously of three IRA volunteers (Operation Flaviusas). Named as Seán Savage, Daniel McCann, and Mairéad Farrell; all were known Volunteers with the Provisional IRA’s Belfast Brigade and all were shot dead while unarmed, at a filling station, in Gibraltar. They had been planning to detonate a bomb during the changing of the guard ceremony, outside the Governor’s residence in Gibraltar.

On June 30th 1988, Belgian police, acting on a tip-off, raided the home of a known IRA sympathiser and arrested Fr. Ryan. Police seized a quantity of bomb-making equipment; instructional manuals, and a large sum of foreign currency. While British authorities provided substantial evidence in support of a request for Fr. Ryan’s extradition from Belgium to face charges in Britain, legal argument between the two countries ensued over the next five months.

Following a three-week hunger strike in protest against his possible extradition to Britain, Belgian police instead transferred Fr. Ryan to Dublin on November 25th 1988. It should be noted that Fr. Ryan vehemently denied all UK claims of terrorist involvement and insisted that no Irish citizen could ever receive a fair trial in the U.K. In October 1989, the Irish director of Public Prosecutions decided that Fr. Ryan should not be extradited to stand trial.

In a secret briefing note to the Irish government, the then twice to be appointed Attorney General (AG) Mr John Murray outlined his concerns: “In the opinion of the AG the effect of the (UK) material which has been published has, manifestly and inescapably, been to create such prejudice and hostility to Patrick Ryan that, were he to be extradited to Britain, it would not be possible for a jury to approach the issue of his guilt or innocence, free from bias.” Instead, he said Fr. Ryan could face action in Ireland under the Criminal Law (Jurisdiction) Act, 1976.

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher now clashed with Taoiseach Charles Haughey over his refusal to extradite, describing Fr. Ryan as a “really bad egg”, “a very dangerous man”, and “a mad priest careering around Europe”. When Mr Haughey told Ms Thatcher that he had never heard of Fr. Ryan until he had appeared in Belgium, she is understood to have replied, “You amaze me. From 1973 to 1984, he was the main channel of contact with the Libyans”. “The failure to secure Ryan’s arrest is a matter of very grave concern to the Government. It is no use governments (Belgium & Ireland) adopting great declarations and commitments about fighting terrorism, if they then lack the resolve to put them into practice.”

Mr Haughey replied: “Fr. Ryan is an extraordinary case. You have a mad priest careering around Europe, arrested in Belgium, and then flown to us in a military plane, avoiding British airspace.” Such public verbal statements made by Margaret Thatcher now merely added further credence to the Irish AG’s ruling decision advising no extradition.

Fr. Ryan would later publicly state that he had raised money both inside and outside Europe for victims on the nationalist side, during the troubles in Northern Ireland, but insisted that he had “never bought explosives for the IRA or anybody else”, and had “never been requested by any paramilitary group to do so”.

The Director of Public Prosecutions in Ireland announced, in October 1989, that he had decided not to initiate proceedings against Fr. Patrick Ryan.

Evil Man